Duolingo: The British Cycling Team of SaaS

The Aggregation of Marginal Gains

In 2003, a man by the name of Dave Brailsford became the performance director of British Cycling. He was charged with improving Britain’s Olympic track cycling team. Up to that point, they had won a single gold medal in their 76-year history. In the 2008 Olympics, they won 7 of the 10 gold medals in track cycling. They repeated that feat again in the London Games in 2012. That is incredible improvement in a rapid time period followed by sustained results.

Britain had also never had a winner of the Tour de France. In 2010, Dave was appointed General Manager Team Sky, Britain’s Tour de France team. A member of his team won the Tour de France for the first time in 2012. They also won the title in 2013, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2019. Again, that is an incredibly rapid ascension to the top, but it is also incredible that they were able to maintain that edge and continue to win.

The way Brailsford achieved this success seems fairly simple. Here is Brailsford’s philosophy as he explained it to the BBC, “The whole principle came from the idea that if you broke down everything you could think of that goes into riding a bike, and then improved it by 1%, you will get a significant increase when you put them all together.” The team was maniacal about finding every single incremental marginal gain possible. This included obvious performance-based metrics like monitoring and measuring a cyclists power output throughout training exercises. However, it extended far beyond just cycling itself. Training regimens and diet were also a part of it, but they got down to really fine details. Here are some examples of the things that they did that he shared with the Harvard Business Review:

By experimenting in a wind tunnel, we searched for small improvements to aerodynamics. By analyzing the mechanics area in the team truck, we discovered that dust was accumulating on the floor, undermining bike maintenance. So we painted the floor white, in order to spot any impurities. We hired a surgeon to teach our athletes about proper hand-washing so as to avoid illnesses during competition (we also decided not to shake any hands during the Olympics). We were precise about food preparation. We brought our own mattresses and pillows so our athletes could sleep in the same posture every night. We searched for small improvements everywhere and found countless opportunities. Taken together, we felt they gave us a competitive advantage.

That process of aggregating marginal gains led to a world-class cycling team.

Duolingo is the British Cycling Team of SaaS

What makes Duolingo unique among the companies I follow is their commitment to continuous incremental improvements. Duolingo is primarily a language learning app. It’s a software-as-a-service (SaaS) company that sells directly to consumers mostly through a paid subscription model to use premium features on the app. I’ve learned two foreign languages (both before Duolingo was a thing) and the stark truth about language learning is that the only way to truly learn one is by grinding away and getting in a huge amount of practice. When I was learning German (my first foreign language), I was told that to truly become fluent, you had to make about 10,000 mistakes.

I’m not sure on the actual number, but directionally, that’s true. To make that many mistakes you need to get in a ton of repetitious practice. Duolingo’s moat, what sets them apart from the competition, is that they have designed an interactive learning platform that takes away the monotony of learning things like a foreign language. They help people have fun and stay engaged while making their 10,000 mistakes.

What makes them special is the same thing that made the British Cycling team successful, a maniacal focus on marginal gains. One of Duolingo’s core operating principles is to “Test everything”. And they mean everything. They are constantly running A/B tests to optimize user experience, monetization, UX/UI, ad campaigns. You name it, they’ve tested it. Here is how one employee put it:

Think of any feature that you’ve come across while using Duolingo. Animated skill icons? The result of an experiment. Adding five new leagues to the Leaderboard? Also the result of an experiment. The amount of tears that our owl mascot, Duo, cries in your inbox when you forget to do your lessons? You guessed it.

The result is that they get data like this that shows how many sessions their users start:

And how many they finish:

And all the data in between. They run statistical analysis on all this data and are constantly optimizing everything in the app that makes a difference for the user and the monetization. Here is an example of an experiment they ran that allowed users to tap on skills while offline (a previously unavailable action, the icons would just be grayed out). When they clicked, it gave them an ad to purchase the capability to get Duolingo Plus, which allows them to do offline lessons. Here is the data that came from it:

It was successful in greater monetization…but they also found that it led to a decrease in user retention. They decided not to implement the feature because “We never want to launch new features that negatively impact learning habits and behavior, so even though this experiment was successful from a revenue standpoint, we decided to shut it down and iterate on it.” This also highlights that they value the long-term health of the business over short-term gains, which is something I find very important in the companies I invest in.

They run A/B tests on different marketing techniques, ads, geographies, subscription price points, new lessons, new skills, email campaigns, social media. If you can test it, they do. Each of these tests lead to cumulative 1% improvements the in-app experience, monetization, marketing, and help them continuously iterate on the product. It’s a virtuous cycle that leads to more optimal outcomes.

Constant course adjustments lead to an optimal path to success

All companies exist and operate in a changing landscape. What works in one macroenvironment may not work in another. What works with Millennials may not be the same with Gen Z. The way you monetize people in the US is different than Japan or Germany. There are an innumerable amount of variables that constantly change the playing field. That means even if you know the destination of what you want your company and product to be, the path to get there is consistently changing. Consistent small course corrections keeps you from charting a course that will lead the company off a cliff or into impassable terrain. It helps you plot the optimal path through the tortuous path of the shifting marketplace to meet your goals.

What about the Data?

Ok, so that’s the thesis. Is that actually what is going on with the company? This is why I call this data driven investing. The point is to form a thesis, then check the data to see if it confirms the thesis. I want the companies I invest in to have high growth, improving margins, a widening moat, and be at least reasonably priced. Specific to Duolingo, the thesis above should result in greater app engagement over time and greater revenue per user. This would show that the app becomes more engaging and they get better monetization through their marginal gains.

Growth

Revenue, gross profit, free cash flow, and net income are all trending up over time. Topline growth is exceptionally consistent. Since going public in 2Q21, topline growth has stayed in a range from 40.6% to 51.3% for three straight years. Free Cash Flow (FCF) is a little lumpy, but Duolingo is a consistent growth monster.

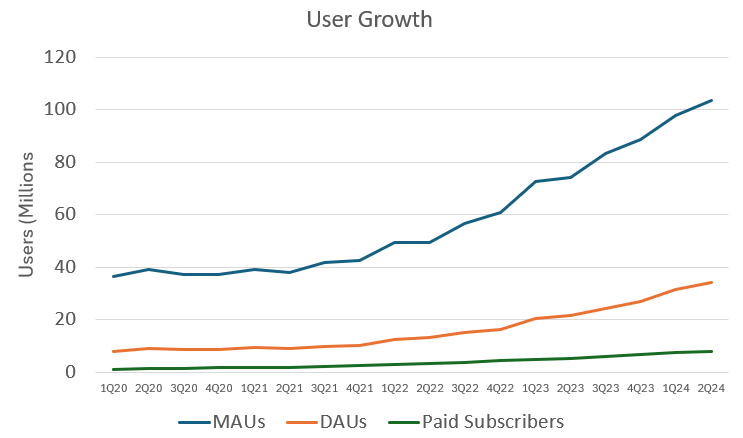

They also grow users like crazy. Both the revenue graph above and the user growth graph below are textbook exponential curves. MAUs are monthly active users, DAUs are daily active users and paid subscribers is self-explanatory.

Steady consistent secular growth is a hallmark of Duolingo.

Margins

Gross profit margins are rock steady, indicating that they are not really seeing any competitors eating away at their pricing power. As they’ve scaled the business and take advantage of efficiencies of scale, their FCF margins and net income margins are consistently climbing. The fact that they are still growing revenue at a 40%+ clip and they’ve already had a quarter with greater than 40% FCF margins is nuts.

Duolingo has the potential to be an extremely high margin company that rewards investors with huge cash flows for many years into the future.

Moat

Many are concerned about the disruptive potential of AI in the language learning space. It is a risk, but if AI were disrupting the business right now, I think you’d have seen it in the gross margins as competitors erode their pricing power. That hasn’t materialized at all. It’s something to keep an eye on, but I’d say if anything the moat is actually expanding. I’ll revisit this point and expand it into an article all of its own in the future.

Engagement and Monetization

Ok, so is the thesis above true? It appears obvious that the top of the funnel is working as they are adding users at a crazy high clip. Are they just paying exorbitant marketing expenses for all these new users, or are they seeing marketing efficiencies because of word of mouth and the product getting better? Here is their Sales and Marketing (S&M) spend per new monthly active user (I use trailing twelve month numbers to smooth things out over a year because it can be volatile from quarter to quarter). Marketing efficiency shows a consistent downward trend as they pay less over time for each new user.

Users are also becoming more engaged over time. Here is the ratio of DAUs to MAUs.

More users are being converted from casual users who only use it monthly to daily users. This is almost certainly the result of the aggregation of marginal gains we discussed above. The app keeps people engaged. The next logical question is if they are them monetizing these members at a higher rate over time.

They’ve increased the rate of subscribers per MAU by over 50% since going public in Q3 2021. The data support the theory that incremental gains make the app stickier, more engaging, and lead to greater overall monetization.

Valuation

I want to buy great companies at reasonable prices. I’d love it if they were available cheap, but I’d rather slightly overpay for an exceptional company than underpay for a mediocre one. Valuation is one of the last things I look at and as long as it seems reasonable, I feel comfortable buying.

Valuation is always going to be somewhat subjective. To convince myself of the valuation here, I’ve looked at PEG, used a reverse DCF, gross profit/growth metrics, and other things. Rather than go through all of that, I think it is best expressed by looking at the Rule of 40. For Duolingo and other SaaS companies, I think the rule of 40 is the best overall metric to use to judge the health of the business. The rule of 40 calculation is simple. You take either free cash flow or adjusted EBITDA margins, add revenue growth rate, and if the total of those two numbers is greater than 40, then you have an excellent SaaS company. It illustrates that you can either be a high growth company with lower margins and be successful or a lower growth company with high margins and be successful. Duolingo, based on last quarter’s results, has a Rule of 40 score of 67.6, which is the highest of any public SaaS company of which I am aware. Based on that high rule of 40 number, they should get a premium relative to other SaaS companies who score lower. Here’s a graph showing the Rule of 40 score vs. estimated FWD price/sales for some of the biggest names in SaaS.

The best place to be on this graph is at the bottom right. You know…right where Duolingo is. If it were to revert to the average trendline, it would trade at a P/S of 16, which would equate to a stock price of $306, a 44% premium from where it trades on the day I’m writing this. Duolingo is also the only SaaS company in the market that I’m aware of who is GAAP profitable, grew at a rate of at least 40% last year, and is predicted to grow at a 30% or greater rate this year (the projections have them at 38% growth). In terms of execution, this is the best SaaS company in the stock market, and they are available at what I’d consider an undervalued price relative to similar businesses.

Conclusion

I built the majority of my Duolingo position in 2023 and my average is in the low $100s. It used to be under $100, but I added more recently as the stock fell below $180. I feel like I have a full position at this point and will only add when I feel it is underpriced, as I did recently. It’s one of my top five positions and I feel very confident holding it and think it’s an exceptional company that will lead to excellent returns in the years to come.

Subscriber update

Right now I am comfortable with taking the time to write about 2 articles every month. Once I get to 100 paid subscribers, I’ll start a YouTube channel and do at least one video every other week (I plan on also posting those on X).

Paid subscribers also get access to a private X chat. If you are a paid subscriber and not in the chat, please email me at datadinvesting@gmail.com and let me know and I’ll get you added. If you have any other ideas for things I can do to bring value to my paid subscribers, don’t hesitate to reach out.

Disclosures: I am long DUOL, PLTR, and CRWD.

The information contained in this article is for informational purposes only. You should not construe any such information as legal, tax, investment, financial, or other advice. None of the information in this article constitutes a solicitation, recommendation, endorsement, or offer by the author, its affiliates or any related third party provider to buy or sell any securities or other financial instruments in any jurisdiction in which such solicitation, recommendation, endorsement, or offer would be unlawful under the securities laws of such jurisdiction.

I am struggling with this. As I read your thesis, all I keep hearing in my head is "the best company at the wrong price makes for a bad investment".

Gross margins above 70% are awesome, but OPEX is eyewatering. For the past five full financial years, the combination of SG&A and R&D consumed all of the gross profit and then some. Said differently, the company is loss making which doesn't bode well for shareholders. To make matters worse, they are constantly issuing stock and so diluting shareholders (13% dilution since 2021).

Digging deeper, and the free cash flow numbers aren't what they seem to be. A huge part of the cash from operations on the cash flow statement is the result of adding in unearned revenue - what kind of accounting alchemy is this?

To make matters worse, the company extracting stock based compensation booked in FY23 as 6x net income (it will invariably be far more once it vests!)

This is a business being run for the benefit of insiders at the expense of shareholders.

This kind of investment should come with a health warning attached - or more appropriately, a 'wealth warning' attached. This is a conduit for transferring wealth from shareholders to insiders. It is highly unlikely to end well for outsiders.

I wouldn't touch it. Just my view. Best of luck if you take a counter view.

Great read! Is their move into other learning areas like maths part of your thesis?